Bruce Sterling's Catscan Columns

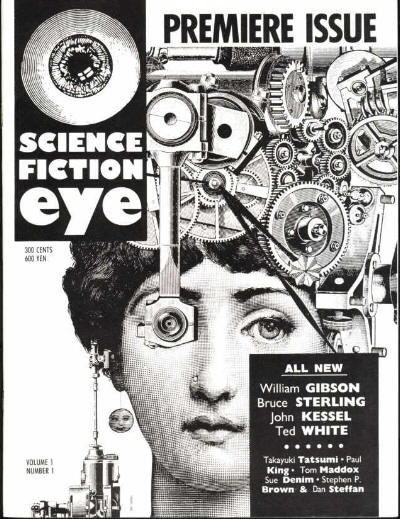

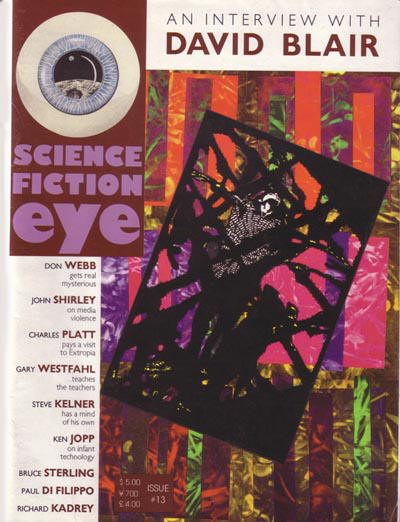

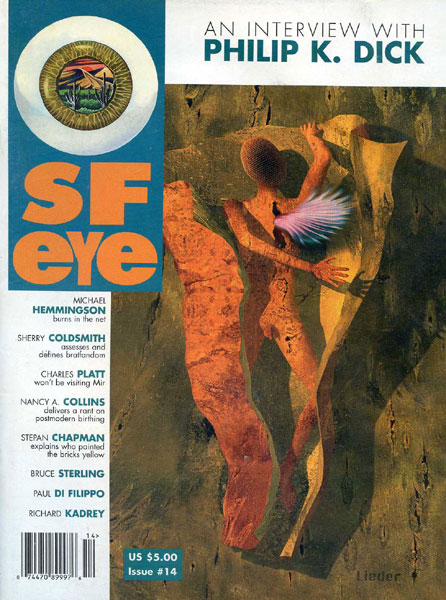

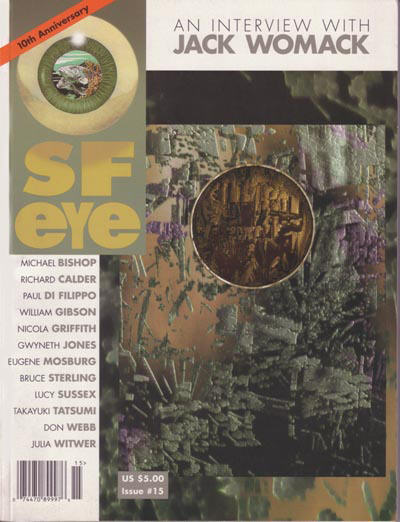

Written for Science Fiction Eye, an US Amateur Magazine of science-fiction criticism and review that published fifteen issues, from Winter [January] 1987 to Fall 1997. The magazine was edited by Stephen P. Brown and Daniel Steffan.

Contents:

- 1. Midnight on the Rue Jules Verne

- 2. The Spearhead of Cognition

- 3. Updike's Version

- 4. The Agberg Ideology

- 5. Slipstream

- 6. Shinkansen

- 7. My Rihla

- 8. Cyber-Superstition

- 9. Digital Dolphins in the Dance of Biz

- 10. A Statement of Principle

- 11. Sneaking For Jesus 2001

- 12. Return to the Rue Jules Verne

- 13. Electronic Text

- 14. Memories of the Space Age

- 15. Big Science - The Year in Review

Midnight on the Rue Jules Verne

Catscan #1

Publication: Science Fiction Eye, #1

Date: Winter 1987

Editors: Stephen P. Brown, Daniel J. Steffan

Publisher: 'Til You Go Blind Cooperative

Price: $3.00

Pages: 72

Cover: Dan Steffan

A kind of SF folk tradition surrounds the founding figure of Jules Verne. Everyone knows he was a big cheese back when the modern megalopolis of SFville was a 19th-century village. There's a bronze monument to him back in the old quarter of town, the Vieux Carre. You know, the part the French built, back before there were cars.

At midnight he stands there, somewhat the worse for the acid rain and the pigeons, his blind bronze eyes fixed on a future that has long since passed him by. SFville's citizenry pass him every day without a thought, their attention fixed on their daily grind in vast American high-rises; if they look up, they are intimidated by the beard, the grasped lapel, the flaking reek of Victorian obsolescence.

Everyone here knows a little about old Jules. The submarine, the moon cannon, the ridiculously sluggish eighty days. When they strip up the tarmac, you can still see the cobbles of the streets he laid. It's all still there, really, the village grid of SFville, where Verne lived and worked and argued scientific romance with the whippersnapper H.G. Wells. Those of us who walk these mean streets, and mutter of wrecking balls and the New Jerusalem, should take the time for a look back. Way back. Let's forget old Jules for the moment. What about young Jules?

Young Jules Verne was trouble. His father, a prosperous lawyer in the provincial city of Nantes, was gifted with the sort of son that makes parents despair. The elder Verne was a reactionary Catholic, given to frequent solitary orgies with the penitential scourge. He expected the same firm moral values in his heir.

Young Jules wanted none of this. It's sometimes mentioned in the SF folktale that Jules tried to run away to sea as a lad. The story goes that he was recaptured, punished, and contritely promised to travel henceforth "only in his imagination." It sounds cute. It was nothing of the kind. The truth of the matter is that the eleven-year-old Jules resourcefully bribed a cabin-boy of his own age, and impersonated his way onto a French merchant cruiser bound for the Indies. In those days of child labor, the crew accepted Jules without hesitation. It was a mere fluke that a neighbor happened to spot Jules during his escape and informed against him. His father had to chase him down in a fast chartered steam-launch.

This evidence of mulishness seems to have thrown a scare into the Verne family, and in years to come they would treat Jules with caution. Young Jules never really broke with his parents, probably because they were an unfailing source of funds. Young Jules didn't much hold with wasting time on day-jobs. He was convinced that he was possessed of genius, despite the near-total lack of hard evidence.

During his teens and twenties, Jules fell for unobtainable women with the regularity of clockwork. Again and again he was turned down by middle-class nymphs whose parents correctly assessed him as an art nut and spoiled ne'er-do-well.

Under the flimsy pretext of studying law, Jules managed to escape to Paris. He had seen the last of stuffy provincial France, or so he assumed: "Well," he wrote to a friend, "I'm leaving at last, as I wasn't wanted here, but one day they'll see what stuff he was made of, that poor young man they knew as Jules Verne."

The "poor young man" rented a Parisian garret with his unfailing parental stipend. He soon fell in with bad company—namely, the pop-thriller writer Alexandre Dumas Pere (author of Count of Monte Cristo, The Three Musketeers, about a million others.) Jules took readily to the role of declasse' intellectual and professional student. During the Revolution of 1848 he passed out radical political pamphlets on Paris streetcorners. At night, embittered by female rejection, he wrote sarcastic sonnets on the perfidy of womankind. Until, that is, he had his first affair with an obliging housemaid, one of Dumas' legion of literary groupies. After this, young Jules loosened up to the point of moral collapse and was soon, by his own admission, a familiar figure in all the best whorehouses in Paris.

This went on for years. Young Jules busied himself writing poetry and plays. He became a kind of gofer for Dumas, devoting vast amounts of energy to a Dumas playhouse that went broke. (Dumas had no head for finance—he kept his money in a baptismal font in the entryway of his house and would stuff handfuls into his pockets whenever going out.)

A few of Jules' briefer pieces—a domestic farce, an operetta—were produced, to general critical and popular disinterest. During these misspent years Jules wrote dozens of full-length plays, most of them never produced or even published, in much the vein of would-be Hollywood scriptwriters today. Eventually, having worked his way into the theatrical infrastructure through dint of prolonged and determined hanging-out, Jules got a production job in another playhouse, for no salary to speak of. He regarded this as his big break, and crowed vastly to his family in cheerful letters that made fun of the Pope.

Jules moved in a fast circle. He started a literary-artistic group of similar souls, a clique appropriately known as the Eleven Without Women. Eventually one of the Eleven succumbed, and invited Jules to the wedding. Jules fell immediately for the bride's sister, a widow with two small daughters. She accepted his proposal. (Given Jules' record, it is to be presumed that she took what she could get.)

Jules was now married, and his relentlessly unimaginative wife did what she could to break him to middle-class harness. Jules' new brother-ln-law was doing okay in the stock market, so Jules figured he would give it a try. He extorted a big loan from his despairing father and bought a position on the Bourse. He soon earned a reputation among his fellow brokers as a cut-up and general weird duck. He didn't manage to go broke, but a daguerreotype of the period shows his mood. The extended Verne family sits stiffly before the camera. Jules is the one in the back, his face in a clown's grimace, his arm blurred as he waves wildly in a brokerage floor "buy" signal.

Denied his longed-for position in the theater, Jules groaningly decided that he might condescend to try prose. He wrote a couple of stories heavily influenced by Poe, a big period favorite of French intellectuals. There was a cheapo publisher in town who was starting a kid's pop-science magazine called "Family Museum." Jules wrote a couple of pieces for peanuts and got cover billing. The publisher decided to try him out on books. Jules was willing. He signed a contract to do two books a year, more or less forever, in exchange for a monthly sum.

Jules, who liked hobnobbing with explorers and scientists, happened to know a local deranged techie called Nadar. Nadar's real name was Felix Tournachon, but everybody called him Nadar, for he was one of those period Gallic swashbucklers who passed through life with great swirlings of scarlet and purple and the scent of attar of roses. Nadar was involved in two breaking high-tech developments of the period: photography and ballooning. (Nadar is perhaps best remembered today as the father of aerial photography.)

Nadar had Big Ideas. Jules' real forte was geography—a date-line or a geodesic sent him into raptures—but he liked Nadar's style and knew good copy when he saw it. Jules helped out behind the scenes when Nadar launched THE GIANT, the largest balloon ever seen at the time, with a gondola the size of a two-story house, lavishly supplied with champagne. Jules never rode the thing—he had a wife and kids now—but he retired into his study with the plot-line of his first book, and drove his wife to distraction. "There are manuscripts everywhere—nothing but manuscripts," she said in a fine burst of wifely confidence. "Let's hope they don't end up under the cooking pot."

Five Weeks In A Balloon was Jules' first hit. The thing was a smash for his publisher, who sold it all over the world in lavish foreign editions for which Jules received pittances. But Jules wasn't complaining—probably because he wasn't paying attention.

With a firm toehold in the public eye, Jules soon hit his stride as a popular author. He announced to the startled stockbrokers: "Mes enfants, I am leaving you. I have had an idea, the sort of idea that should make a man's fortune. I have just written a novel in a new form, one that's entirely my own. If it succeeds, I shall have stumbled upon a gold mine. In that case, I shall go on writing and writing without pause, while you others go on buying shares the day before they drop and selling them the day before they rise. I am leaving the Bourse. Good evening, mes enfants."

Jules Verne had invented hard science fiction. He originated the hard SF metier of off-the-rack plots and characters, combined with vast expository lumps of pop science. His innovation came from literary naivete; he never learned better or felt any reason to. (This despite Apollinaire's sniping remark: "What a style Jules Verne has, nothing but nouns.")

Verne's dialogue, considered quite snappy for the period, was derived from the stage. His characters constantly strike dramatic poses: Ned Land with harpoon upraised, Phileas Fogg reappearing stage-right in his London club at the last possible tick of the clock. The minor characters—comic Scots, Russians, Jews—are all stage dialect and glued-on beards, instantly recognizable to period readers, yet fresh because of cross-genre effects. They brought a proto-cinematic flash to readers used to the gluey, soulful character studies of, say, Stendhal.

The books we remember, the books determined people still occasionally read, are products of Verne in his thirties and forties. (His first novel was written at thirty-five.) In these early books, flashes of young Jules' student radicalism periodically surface for air, much like the Nautilus. The character of Captain Nemo, for instance, is often linked to novelistic conventions of the Byronic hero. Nemo is, in fact, a democratic terrorist of the period of '48, the year when the working-class flung up Paris barricades, and, during a few weeks of brief civil war, managed to kill off more French army officers than were lost in the entire Napoleonic campaigns. The uprising was squelched, but Jules' generation of Paris '48, like that of May '68, never truly forgot.

Jules did okay by his "new form of the novel." He eventually became quite wealthy, though not through publishing, but the theater. (Nowadays it would be movie rights, but the principle still stands.) Jules, incidently, did not write the stage versions of his own books; they were done by professional theater hacks. Jules knew the plays stank, and that they travestied his books, but they made him a fortune. The theatrical version of his mainstream smash, Michael Strogoff, included such lavish special effects as a live elephant on stage. It was so successful that the term "Strogoff" became contemporary Paris slang for anything wildly bravissimo.

Fortified with fame and money, Jules lunged against the traces. He travelled to America and Scandinavia, faithfully toting his notebooks. He bought three increasingly lavish yachts, and took to sea for days at a time, where he would lie on his stomach scribbling Twenty Thousand Leagues against the deck.

During the height of his popularity, he collected his family and sailed his yacht to North Africa, where he had a grand time and a thrilling brush with guntoting Libyans. On the way back, he toured Italy, where the populace turned out to greet him with fireworks and speeches. In Rome, the Pope received him and praised his books because they weren't smutty. His wife, who was terrified of drowning, refused to get on the boat again, and eventually Verne sold it.

At his wife's insistence, Jules moved to the provincial town of Amiens, where she had relatives. Downstairs, Mme. Verne courted local society in drawing rooms crammed with Second Empire bric-a-brac, while Jules isolated himself upstairs in a spartan study worthy of Nemo, its wall lined with wooden cubbyholes full of carefully labeled index-cards. They slept in separate bedrooms, and rumor says Jules had a mistress in Paris, where he often vanished for weeks.

Jules' son Michel grew up to be a holy terror, visiting upon Jules all the accumulated karma of his own lack of filial piety. The teenage Michel was in trouble with cops, was confined in an asylum, was even banished onto a naval voyage. Michel ended up producing silent films, not very successfully. Jules' stepdaughters made middle-class marriages and vanished into straitlaced Catholic domesticity, where they cooked up family feuds against their scapegrace half-brother.

Verne's work is marked by an obsession with desert islands. Mysterious Isles, secret hollow volcanoes in the mid-Atlantic, vast ice-floes that crack off and head for the North Pole. Verne never really made it into the bosom of society. He did his best, and played the part whenever onstage, but one senses that he knew somehow that he was Not Like The Others and might be torn to pieces if his facade cracked. One notes his longing for the freedom of empty seas and skies, for a submarine full of books that can sink below storm level into eternal calm, for the hollow shell fired into the pristine unpeopled emptiness of circumlunar space.

From within his index-card lighthouse, the isolation began to tell on the aging Jules. He had now streamlined the production of novels to industrial assembly-work, so much so that lying gossip claimed he used a troop of ghostwriters. He could field-strip a Verne book blindfolded, with a greased slot for every part—the daffy scientist, the comic muscleman or acrobat, the ordinary Joe who asks all the wide-eyed questions, the woman who scarcely exists and is rescued from suttee or sharks or red Indians. Sometimes the machine is the hero—the steam-driven elephant, the flying war-machine, the gigantic raft—sometimes the geography: caverns, coal-mines, ice-floes, darkest Africa.

Bored, Jules entered politics, and joined the Amiens City Council, where he was quickly shuffled onto the cultural committee. It was a natural sinecure and he did a fair job, getting electric lights installed, widening a few streets, building a municipal theater that everyone admired and no one attended. His book sales slumped steadily. The woods were full of guys writing scientific romances by now—people who actually knew how to write novels, like Herbert Wells. The folk-myth quotes Verne on Wells' First Men In The Moon: "Where is this gravity-repelling metal? Let him show it to me." If not the earliest, it is certainly the most famous exemplar of the hard-SF writer's eternal plaint against the fantasist.

The last years were painful. A deranged nephew shot Verne in the foot, crippling him; it was at this time that he wrote one of his rare late poems, the "Sonnet to Morphine." He was to have a more than nodding acquaintance with this substance, though in those days of children's teething-laudanum no one thought much of it. He died at seventy-seven in the bosom of his vigorously quarrelling family, shriven by the Church. Everyone who had forgotten about him wrote obits saying what a fine fellow he was. This is the Verne everyone thinks that they remember: the greybearded paterfamilias, the conservative Catholic hardware-nut, the guy who made technical forecasts that Really Came True if you squint real hard and ignore most of his work.

Jules Verne never knew he was "inventing science fiction," in the felicitous phrase of Peter Costello's insightful 1978 biography. He knew he was on to something hot, but he stepped onto a commercial treadmill that he didn't understand, and the money and the fame got to him. The early artistic failures, the romantic rejections, had softened him up, and when the public finally Recognized His Genius he was grateful, and fell into line with their wishes.

Jules had rejected respectability early on, when it was offered to him on a plate. But when he had earned it on his own, everyone around him swore that respectability was dandy, and he didn't dare face them down. Wanting the moon, he ended up with a hatch-battened one-man submarine in an upstairs room. Somewhere along the line his goals were lost, and he fell into a role his father might almost have picked for him: a well-to-do provincial city councilman. The garlands disguised the reins, and the streetcorner radical with a headful of visions became a dusty pillar of society.

This is not what the world calls a tragedy; nor is it any small thing to have books in print after 125 years. But the path Young Jules blazed, and the path Old Jules was gently led down, are still well-trampled streets here in SFville. If you stand by his statue at midnight, you can still see Old Jules limping home, over the cobblestones. Or so they say.

The Spearhead of Cognition

Catscan #2

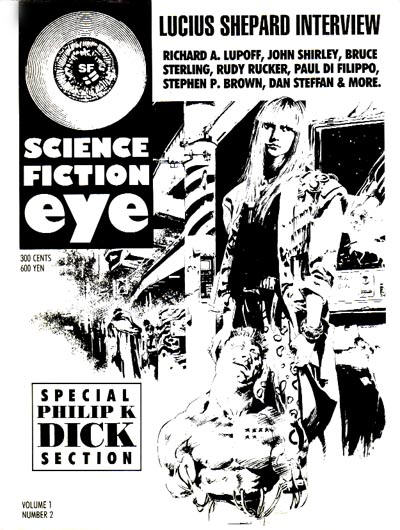

Publication: Science Fiction Eye, #2

Date: August 1987

Editors: Stephen P. Brown, Daniel J. Steffan

Publisher: 'Til You Go Blind Cooperative

Price: $3.00

Pages: 72

Cover: Jun Suemi

You're a kid from some podunk burg in Alabama.

From childhood you've been gnawed by vague numinous sensations and a moody sense of your own potential, but you've never pinned it down.

Then one joyful day you discover the work of a couple of writers. They're pretty well-known (for foreigners), so their books are available even in your little town. Their names are "Tolstoy" and "Dostoevsky." Reading them, you realize: This is it! It's the sign you've been waiting for! This is your destiny—to become a Russian Novelist!

Fired with inspiration, you study the pair of 'em up and down, till you figure you've got a solid grasp of what they're up to. You hear they're pretty well-known back in Russia, but to your confident eye they don't seem like so much. (Luckily, thanks to some stunt of genetics, you happen to be a genius.) For you, following their outline seems simple enough—in a more sophisticated vein, of course, and for a modern audience. So you write a few such books, you publish 'em, and people adore them. The folks in 'Bama are fit to bust with pride, and say you've got Tolstoy beat all hollow.

Then, after years of steadily growing success, strange mail arrives. It's from Russia! They've been reading your stuff in translation, and you've been chosen to join the Soviet Writers' Union! Swell! you think. Of course, living in backwoods Alabama, it's been a little tough finding editions of contemporary Russian novelists. But heck, Tolstoy did his writing years ago! By now those Russians must be writing like nobody's business!

Then a shipment of modern Russian novels arrives, a scattering of various stuff that has managed to elude the redtape. You open 'em up and—ohmiGod! It's… it's COMMUNISM! All this stupid stereotyped garbage! About Red heroes ten feet tall, and sturdy peasants cheering about their tractors, and mothers giving sons to the Fatherland, and fathers giving sons to the Motherland… Swallowing bile, you pore through a few more at random—oh God, it's awful.

Then the Literary Gazette calls from Moscow, and asks if you'd like to make a few comments about the work of your new comrades. "Why sure!" you drawl helpfully. "It's clear as beer-piss that y'all have gotten onto the wrong track entirely! This isn't literature—this is just a lot of repetitive agitprop crap, dictated by your stupid oppressive publishers! If Tolstoy was alive today, he'd kick your numb Marxist butts! All this lame bullshit about commie heroes storming Berlin and workers breaking production records—those are stupid power-fantasies that wouldn't fool a ten-year-old! You wanna know the true modern potential of Russian novels? Read some of my stuff, if you can do it without your lips moving! Then call me back."

And sure enough, they do call you back. But gosh—some of the hardliners in the Writers' Union have gone and drummed you out of the regiment. Called you all kinds of names… said you're stuck-up, a tool of capitalism, a no-talent running-dog egghead. After that, you go right on writing, even criticism, sometimes. Of course, after that you start to get MEAN.

This really happened.

Except that it wasn't Tolstoy and Dostoevsky. It was H.G. Wells and Olaf Stapledon. It wasn't Russian novels, it was science fiction, and the Writers' Union was really the SFWA. And Alabama was Poland.

And you were Stanislaw Lem.

Lem was surgically excised from the bosom of American SF back in 1976. Since then plenty of other writers have quit SFWA, but those flung out for the crime of being a commie rat-bastard have remained remarkably few. Lem, of course, has continued to garner widespread acclaim, much of it from hifalutin' mainstream critics who would not be caught dead in a bookstore's skiffy section. Recently a collection of Lem's critical essays, Macroworlds, has appeared in paperback. For those of us not privy to the squabble these essays caused in the '70s, it makes some eye-opening reading.

Lem compares himself to Crusoe, stating (accurately) that he had to erect his entire structure of "science fiction" essentially from scratch. He did have the ancient shipwrecked hulls of Wells and Stapledon at hand, but he raided them for tools years ago. (We owe the collected essays to the beachcombing of his Man Friday, Austrian critic Franz Rottensteiner.)

These essays are the work of a lonely man. We can judge the fervor of Lem's attempt to reach out by a piece like "On the Structural Analysis of Science Fiction:" a Pole, writing in German, to an Austrian, about French semantic theory. The mind reels. After this superhuman effort to communicate, you'd think the folks would cut Lem some slack—from pure human pity, if nothing else.

But Lem's ideology—both political and literary—is simply too threatening. The stuff Lem calls science fiction looks a bit like American SF—about the way a dolphin looks like a mosasaur. A certain amount of competitive gnawing and thrashing was inevitable. The water roiled ten years ago, and the judgement of evolution is still out. The smart money might be on Lem. The smarter money yet, on some judicious hybridization. In any case we would do well to try to understand him.

Lem shows little interest in "fiction" per se. He's interested in science: the structure of the world. A brief autobiographical piece, "Reflections on My Life," makes it clear that Lem has been this way from the beginning. The sparkplug of his literary career was not fiction, but his father's medical texts: to little Stanislaw, a magic world of skeletons and severed brains and colorful pickled guts. Lem's earliest "writings," in high school, were not "stories," but an elaborate series of imaginary forged documents: "certificates, passports, diplomas… coded proofs and cryptograms… "

For Lem, science fiction is a documented form of thought-experiment: a spearhead of cognition.

All else is secondary, and it is this singleness of aim that gives his work its driving power. This is truly "a literature of ideas," dismissing the heart as trivial, but piercing the skull like an ice-pick.

Given his predilections, Lem would probably never have written "people stories." But his rationale for avoiding this is astounding. The mass slaughters during the Nazi occupation of Poland, Lem says, drove him to the literary depiction of humanity as a species. "Those days have pulverized and exploded all narrative conventions that had previously been used in literature. The unfathomable futility of human life under the sway of mass murder cannot be conveyed by literary techniques in which individuals or small groups of persons form the core of the narrative."

A horrifying statement, and one that people in happier countries would do well to ponder. The implications of this literary conviction are, of course, extreme. Lem's work is marked by unflinching extremities. He fights through ideas with all the convulsive drive of a drowning man fighting for air. Story structure, plot, human values, characterization, dramatic tension, all are ruthlessly trudgeon-kicked aside.

In criticism, however, Lem has his breath, and can examine the trampled flotsam with a cynical eye. American SF, he says, is hopelessly compromised, because its narrative structure is trash: detective stories, pulp thrillers, fairy-tales, bastardized myths. Such outworn and kitschy devices are totally unsuited to the majestic scale of science fiction's natural thematics, and reduce it to the cheap tricks of a vaudeville conjurer.

Lem holds this in contempt, for he is not a man to find entertainment in sideshow magic. Stanislaw Lem is not a good-time guy. Oddly, for a science fiction writer, he seems to have very little interest in the intrinsically weird. He shows no natural appetite for the arcane, the offbeat, the outre.. He is colorblind to fantasy. This leads him to dismiss much of the work of Borges, for example. Lem claims that "Borges' best stories are constructed as tightly as mathematical proofs." This is a tautology of taste, for, to Lem, mathematical proofs are the conditions to which the "best" stories must necessarily aspire.

In a footnote to the Borges essay Lem makes the odd claim that "As soon as nobody assents to it, a philosophy becomes automatically fantastic literature." Lem's literature is philosophy; to veer from the path of reason for the sake of mere sensation is fraudulent.

American SF, therefore, is a tissue of frauds, and its practicioners fools at best, but mostly snake-oil salesmen. Lem's stern puritanism, however, leaves him at sea when it comes to the work of Philip K. Dick: "A Visionary Among the Charlatans." Lem's mind was clearly blown by reading Dick, and he struggles to find some underlying weltanschauung that would reduce Dick's ontological raving to a coherent floor-plan. It's a doomed effort, full of condescension and confusion, like a ballet-master analyzing James Brown.

Fiction is written to charm, to entertain, to enlighten, to convey cultural values, to analyze life and manners and morals and the nature of the human heart. The stuff Stanislaw Lem writes, however, is created to burn mental holes with pitiless coherent light. How can one do this and still produce a product resembling "literature?" Lem tried novels. Novels, alas, look odd without genuine characters in them. Then he hit on it: a stroke of genius.

The collections A Perfect Vacuum and Imaginary Magnitudes are Lem's masterworks. The first contains book reviews, the second, introductions to various learned tomes. The "books" discussed or reviewed do not actually exist, and have archly humorous titles, like "Necrobes" by "Cezary Strzybisz." But here Lem has found literary structures—not "stories"—but assemblages of prose, familiar and comfortable to the reader.

Of course, it takes a certain aridity of taste to read a book composed of "introductions," traditionally a kind of flaky appetizer before the main course. But it's worth it for the author's sense of freedom, his manifest delight in finally ridding himself of that thorny fictive thicket that stands between him and his Grail. These are charming pieces, witty, ingenious, highly thought-provoking, utterly devoid of human interest. People will be reading these for decades to come. Not because they work as fiction, but because their form follows function with the sinister elegance of an automatic rifle.

Here Lem has finessed an irrevocable choice. It is a choice every science fiction writer faces. Is the writer to write Real Novels which "only happen to be" science fiction—or create knobby and irreducible SF artifacts which are not true "stories," but visionary texts? The argument in favor of the first course is that Real Readers, i.e. mainstream ones, refuse to notice the nakedly science-fictional. How Lem must chuckle as he collects his lavish blurbs from Time and Newsweek (not to mention an income ranking as one of poor wretched Poland's best sources of foreign exchange.) By disguising his work as the haute-lit exudations of a critic, he has out-conjured the Yankee conjurers, had his cake and eaten it publicly, in the hallowed pages of the NY Review of Books.

It's a good trick, hard to pull off, requiring ideas that burn so brilliantly that their glare is overwhelming. That ability alone is worthy of a certain writhing envy from the local Writers' Union. But it's still a trick, and the central question is still unresolved. What is "science fiction," anyway? And what's it there for?

Updike's Version

Catscan #3

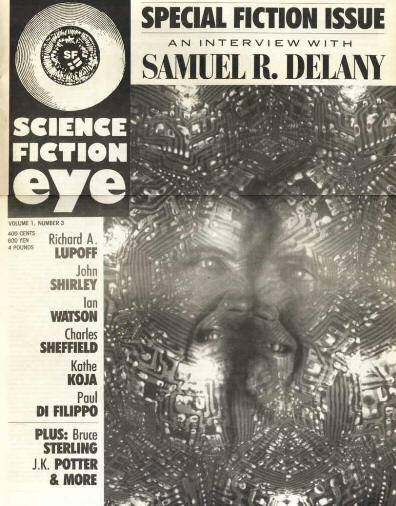

Publication: Science Fiction Eye, #3

Date: March 1988

Editors: Stephen P. Brown, Daniel J. Steffan

Publisher: 'Til You Go Blind Cooperative

Price: $4.00

Pages: 48

Cover: J. K. Potter

John Updike has got to be the epitome of everything that SF readers love to hate. Those slim, clever, etiolated mainstream novels about well-to-do New Yorker subscribers, who sip white wine and contemplate adultery… Novels stuffed like Christmas geese with hi-falutin' literary values… Mention Updike at a SFWA gig, and you get yawns, shudders, shakings of the head… His work affects science fiction writers like cayenne pepper affects a pack of bloodhounds.

Why? Because John Updike has everything SF writers don't. He is, in some very real sense, everything SF writers aren't.

Certain qualities exist, that novelists are popularly supposed to possess. Gifts, abilities, that win An Author respect, that cause folks to back off and gape just a bit if they find one in a grocery line. Qualities like: insight into modern culture. A broad sympathy for the manifold quirks of human nature. A sharp eye for the defining detail. A quick ear for language. A mastery of prose.

John Updike possesses these things. He is erudite. He has, for instance, actually read Isak Dinesen, Wallace Stevens, Ciline, Jean Rhys, Gunter Grass, Nabokov and Bellow. Not only has he read these obscure and intimidating people, but he has publicly discussed the experience with every sign of genuine enjoyment.

Updike is also enormously clever, clever to a point that approaches genius through the sheer irrepressible business of its dexterity. Updike's paragraphs are so brittle, so neatly nested in their comma'ed clauses, that they seem to burst under the impact of the reader's gaze, like hyper-flaky croissants.

Updike sees how things look, notices how people dress, hears how people talk. His eye for the telling detail can make even golf and birdwatching, the ultimate yawnable whitebread Anglo pastimes, more or less interesting. (Okay—not very interesting, granted. But interesting for the sheer grace of Updike's narrative technique. Like watching Fred Astaire take out the garbage.)

It would be enlightening to compare John Updike to some paragon of science fiction writing. Unfortunately no such paladin offers himself, so we'll have to make do with a composite.

What qualities make a great science fiction writer? Let's look at it objectively, putting aside all that comfortable bullshit about the virtues authors are supposed to have. Let's look at the science fiction writer as he is.

Modern culture, for instance. Our SF paladin is not even sure it exists, except as a vaguely oppressive force he's evaded since childhood. He lives in his own one-man splinter culture, and has ever since that crucial time in childhood—when he was sick in bed for two years, or was held captive in the Japanese prison camp, or lived in the Comoros Islands with monstrous parents who were nuts on anthropology or astronomy or Trotsky or religion.

He's pretty much okay now, though, our science fiction author. He can feed himself and sign checks, and he makes occasional supply trips into the cultural anchorage of SF fandom, where he refreshes his soul by looking at people far worse off than he is. But he dresses funny, and mumbles to himself in the grocery line.

While standing there, he doesn't listen to the other folks and make surreptitious authorly notes about dialogue. Far from it: he's too full of unholy fire to pay much attention to mere human beings. And anyway, his characters generally talk about stuff like neutrinos or Taoism.

His eyes are glazed, cut off at the optic nerve while he watches brain-movies. Too many nights in too many cheap con hotels have blunted his sense of aesthetics; his characters live in geodomes or efficiencies or yurts. They wear one-piece jumpsuits because jumpsuits make people one monotonous color from throat to foot, which allows our attention to return to the neutrinos—of which, incidentally, ninety percent of the universe consists, so that the entire visible world of matter is a mere froth, if we only knew.

But he's learned his craft, our science fiction paladin. The real nutcases don't have enough mental horsepower to go where he's gone. He works hard and he thinks hard and he knows what he's doing. He's read Kuttner and Kornbluth and Blish and Knight, and he knows how to Develop an Idea entertainingly and rigorously, and how to keep pages turning meanwhile, and by Christ those are no easy things. So there, Mr. John Updike with your highflown talk of aht and beautieh. That may be okay for you Ivy League pinky-lifters with your sissy bemoaning about the Crisis of Culture… As if there was going to be a culture after the millennial advent of (Biotech) (Cybernetics) (Space Travel) (Robots) (Atomic Energy) (General Semantics) (Dean Drive) (Dianetics)…

So—there's the difference. It exists, for better or worse. None of this is lost on John Updike. He knows about science fiction, not a hell of a lot, but probably vastly more than most science fiction writers know about John Updike. He recognizes that it requires specialized expertise to write good SF, and that there are vast rustling crowds of us on the other side of the cultural spacewarp, writing for Ace Books and Amazing Stories. Updike reads Vonnegut and Le Guin and Calvino and Lem and Wells and Borges, and would probably read anybody else whose prose didn't cause him physical pain. And from this reading, he knows that the worldview is different in SFville… that writers think literature, and that SF writers think SF.

And he knows, too, that it's not T.S. Eliot's world any more, if indeed it ever was T.S. Eliot's world. He knows we live in a world that loves to think SF, and has thought SF ever since Hiroshima, which was the ne plus ultra of Millennial Technological Advents, which really and truly did change the world forever.

So Updike has rolled up his pinstriped sleeves and bent his formidable intelligence in our direction, and lo we have a science fiction novel, Roger's Version by John Updike.

Of course it's not called a science fiction novel. Updike has seen Le Guin and Lem and Vonnegut crawl through the spacewarp into his world. He's seen them wriggle out, somehow, barely, gasping and stinking of rocket fuel. Updike has no reason to place himself in a position they went to great pains to escape. But Roger's Version does feature a computer on its cover, if not a rocketship or a babe in a bubble helmet, and by heaven it is a science fiction novel—and a very good one.

Roger's Version is Updike's version of what SF should be on about. It deals with SF's native conceptual underpinnings: the impact of technology on society. The book is about technolatry, about millennial visionary thinking. This is SF-think as examined by a classic devotee of lit-think.

It's all there, quite upfront and nakedly science fictional. It puzzles mainstream commentators. "It's as though Updike had challenged himself to convert into the flow of his novel the most resistant stuff he could think of," marvels the Christian Science Monitor, alarmed to find a Real Novel that actually deals straightforwardly with real ideas. "The aggressiveness of Updike's imagination is often a marvel," says People, a mag whose utter lack of imagination is probably its premier selling point.

And look at this list of author's credits: Fred Hoyle, Martin Gardner, Gerald Feinberg, Robert Jastrow. Don't tell me Updike's taken the science seriously. But he has—he's not the man to deny the devil his due, especially after writing Witches of Eastwick, which would have been called a fantasy novel if it had been written badly by a nobody.

But enough of this high-flown abstraction—let's get to grips with the book. There's these two guys, see. There's Roger Lambert, a middle-aged professor of theology, a white-wine-sipping adultery-contemplating intellectual New Englander who probably isn't eighty light-years removed from John Updike. Roger's a nasty piece of business, mostly, lecherous, dishonest and petty-minded, and obsessed with a kind of free-floating Hawthornian Protestant guilt that has been passed down for twenty generations up Boston way and hasn't gotten a bit more specific in the meantime.

And then there's Roger Lambert's antagonist, Dale Kohler. Dale's a young computer hacker with pimples and an obnoxious cocksure attitude. If Dale were just a little more hip about it, he'd be a cyberpunk, but for thematic reasons Updike chose to make Dale a born-again Christian. We never really believe this, though, because Dale almost never talks Jesus. He talks AND-OR circuits, and megabytes, and Mandelbrot sets, with all the techspeak fluency Updike can manage, which is considerable. Dale talks God on a microchip, technological transcendence, and he was last seen in Greg Bear's Blood Music where his name was different but his motive and character were identical. Dale is a type. Not just a science fictional type, but the type that creates science fiction, who talks God for the same reason Philip K. Dick talked God. Because it comes with the territory.

Oh yeah, and then we've got some women. They don't amount to much. They're not people, exactly. They're temptresses and symbols.

There's Roger Lambert's wife, Esther, for instance. Esther ends up teaching Dale Kohler the nature of sin, which utterly destroys Dale's annoying moral certitude, and high time, too. Esther does this by the simple expedient of adulterously fucking Dale's brains out, repeatedly and in meticulously related detail, until Dale collapses from sheer weight of original sin.

A good trick. But Esther breezes through this inferno of deviate carnality, none the worse for the experience; invigorated, if anything. Updike tells us an old tale in this: that women are sexuality, vast unplumbed cisterns of it, creatures of mystery, vamps of the carnal abyss. I just can't bring myself to go for this notion, even if the Bible tells me so. I know that women don't believe this stuff.

Then there's Roger Lambert's niece, Verna. I suspect she represents the Future, or at least the future of America. Verna's a sad case. She lives on welfare with her illegitimate mulatto kid, a little girl who is Futurity even more incarnate. Verna listens to pop music, brain-damaging volumes of it. She's cruel and stupid, and as corrupt as her limited sophistication allows. She's careless of herself and others, exults in her degradation, whores sometimes when she needs the cocaine money. During the book's crisis, she breaks her kid's leg in a reckless fit of temper.

A woman reading this portrayal would be naturally enraged, reacting under the assumption that Updike intends us to believe in Verna as an actual human being. But Verna, being a woman, isn't. Verna is America, instead: dreadfully hurt and spiritually degraded, cheapened, teasing, but full of vitality, and not without some slim hope of redemption, if she works hard and does what's best for her (as defined by Roger Lambert). Also, Verna possesses the magic of fertility, and nourishes the future, the little girl Paula. Paula, interestingly, is every single thing that Roger Lambert isn't, i.e. young, innocent, trusting, beautiful, charming, lively, female and not white.

Roger sleeps with Verna. We've seen it coming for some time. It is, of course, an act of adultery and incest, compounded by Roger's complicity in child abuse, quite a foul thing really, and narrated with a certain gloating precision that fills one with real unease. But it's Updike's symbolic gesture of cultural rapprochement. "It's helped get me ready for death," Roger tells Verna afterward. Then: "Promise me you won't sleep with Dale." And Verna laughs at the idea, and tells him: "Dale's a non-turnon. He's not even evil, like you." And gives Roger the kiss of peace.

So, Roger wins, sort of. He is, of course, aging rapidly, and he knows his cultural values don't cut it any more, that maybe they never cut it, and in any case he is a civilized anachronism surrounded by a popcultural conspiracy of vile and rising noise. But at least Dale doesn't win. Dale, who lacks moral complexity and a proper grasp of the true morbidity of the human condition, thinks God can be found in a computer, and is properly nemesized for his hubris. The future may be fucked, but at least Dale won't be doing it.

So it goes, in Roger's Version. It's a good book, a disturbing book. It makes you think. And it's got an edge on it, a certain grimness and virulence of tone that some idiot would probably call "cyberpunk" if Updike were not writing about the midlife crisis of a theology professor.

Roger's Version is one long debate, between Updike's Protestantism and the techno-zeitgeist of the '80s. With great skill, Updike parallels the arcanity of cyberdom and the equally arcane roots of Christian theology. It's good; it's clever and funny; it verges on the profound. The far reaches of modern computer science—chaos theory, fractals, simulationism, statistical physics and so on—are indeed theological in their implications. Some of their spokesmen have a certain evangelical righteousness of tone that could only alarm a cultural arbiter like John Updike. There are indeed heretic gospels inside that machine, just like there were gospels in a tab of LSD, only more so. And it's a legitimate writerly task to inquire about those gospels and wonder if they're any better than the old one.

So John Updike has listened, listened very carefully and learned a great deal, which he parades deftly for his readership, in neatly tended flashes of hard-science exposition. And he says: I've heard it before, and I may not exactly believe in that Old Rugged Cross, but I'm damned if I'll believe these crazy hacker twerps with their jogging shoes.

There's a lot to learn from this book. It deals with the entirety of our zeitgeist with a broad-scale vision that we SF types too often fail to achieve. It's an interesting debate, though not exactly fair: it's muddied with hatred and smoldering jealousy, and a very real resentment, and a kind of self-loathing that's painful to watch.

And it's a cheat, because Dale's "science" has no real intellectual validity. When you strip away the layers of Updike's cyber-jargon, Dale's efforts are only numerology, the rankest kind of dumb superstition. "Science" it's not. It's not even good theology. It's heretic voodoo, and its pre-arranged failure within this book proves nothing about anything.

Updike is wrong. He clings to a rotting cultural fabric that he knows is based on falsehoods, and rejects challenges to that fabric by declaring "well you're another." But science, true science, does learn from mistakes; theologians like Roger Lambert merely further complicate their own mistaken premises.

I remain unconvinced, though not unmoved, by Updike's object lesson. His book has hit hard at my own thinking, which, like that of most SF writers, is overly enamored of the millennial and transcendent. I know that the twentieth century's efforts to kick Updike's Judaeo-Christian WestCiv values have been grim: Stalin's industrial terror, Cambodia's sickening Luddite madness, the convulsions today in Islam… it was all "Year Zero" stuff, attempts to sweep the board clean, that merely swept away human sanity, instead. Nor do I claim that the squalid consumerism of today's "secular-Humanist" welfare states is a proper vision for society.

But I can't endure the sheer snobbish falseness of Updike's New England Protestantism. Never mind that it's the legacy of American letters, that it's the grand tradition of Hawthorne and Melville, that it's what made America great. It's a shuck, ladies and gentlemen. It won't wash. It doesn't own the future; it won't even kiss the future goodbye on its way to the graveyard. It doesn't own our minds any more.

We don't live in an age of answers, but an age of ferment. And today that ferment is reflected faithfully in a literature called science fiction.

SF may be crazy, it may be dangerous, it may be shallow and cocksure, and it should learn better. But in some very real way it is truer to itself, truer to the world, than is the writing of John Updike.

This is what has drawn Updike, almost despite himself, into science fiction's cultural territory. For SF writers, his novel is a lesson and a challenge. A lesson that must be learned and a challenge that must be met.

The Agberg Ideology

Catscan #4

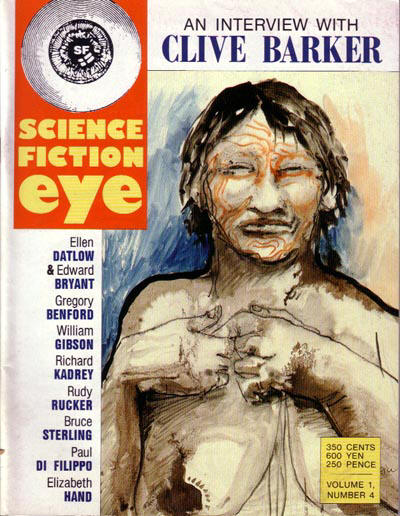

Publication: Science Fiction Eye, #4

Date: August 1988

Editors: Stephen P. Brown, Daniel J. Steffan

Publisher: 'Til You Go Blind Cooperative

Price: $3.50

Pages: 92

Cover: Clive Barker

To speak with precision about the fantastic is like loading mercury with a pitchfork. Yet some are driven to confront this challenge. On occasion, a veteran SF writer will seriously and directly discuss the craft of writing science fiction.

A few have risked doing this in cold print. Damon Knight, for instance. James Blish (under a pseudonym.) Now Robert Silverberg steps deliberately into their shoes, with Robert Silverberg's Worlds of Wonder: Exploring the Craft of Science Fiction (Warner Books, 1987, $17.95).

Here are thirteen classic SF stories by well-known genre authors. Most first appeared in genre magazines during the 1950s. These are stories which impressed Silverberg mightily as he began his career. They are stories whose values he tried hard to understand and assimilate. Each story is followed by Silverberg's careful, analytical notes.

And this stuff, ladies and gents, is the SF McCoy. It's all shirtsleeve, street-level science fiction; every story in here is thoroughly crash-tested and cruises like a vintage Chevy.

Worlds of Wonder is remarkable for its sober lack of pretension. There's no high-tone guff here about how SF should claim royal descent from Lucian, or Cyrano de Bergerac, or Mary Shelley. Credit is given where credit is due. The genre's real founders were twentieth-century weirdos, whacking away at their manual typewriters, with amazing persistence and energy, for sweatshop pay.

They had a definite commonality of interest. Something more than a mere professional fraternity. Kind of like a disease.

In a long, revelatory introduction, Silverberg describes his own first exposure to the vectors of the cultural virus: SF books.

"I think I was eleven, maybe twelve… [The] impact on me was overwhelming. I can still taste and feel the extraordinary sensations they awakened in me: it was a physiological thing, a distinct excitement, a certain metabolic quickening at the mere thought of handling them, let alone reading them. It must be like that for every new reader—apocalyptic thunderbolts and eerie unfamiliar music accompany you as you lurch and stagger, awed and shaken, into a bewildering new world of ideas and images, which is exactly the place you've been hoping to find all your life."

If this paragraph speaks to your very soul with the tongue of angels, then you need this anthology. Buy it immediately, read it carefully. It's full of home truths you won't find anywhere else.

This book is Silverberg's vicarious gift to his younger self, the teenager described in his autobiographical introduction: an itchy, over-bright kid, filled with the feverish conviction that to become a Science Fiction Writer must surely be the moral pinnacle of the human condition.

And Silverberg knows very well that the kids are still out there, and that the virus still spreads. He can feel their hot little hands reaching out plaintively in the dark. And he's willing, with a very genuine magnanimity, to help these sufferers out. Just as he himself was helped by an earlier SF generation, by Mr. Kornbluth, and Mr. Knight, and Mr. and Mrs. Kuttner, and all those other rad folks with names full of consonants.

Silverberg explains his motives clearly, early on. Then he discusses his qualifications to teach the SF craft. He mentions his many awards, his fine reviews, his length of service in the SF field, and, especially, his success at earning a living. It's a very down-home, pragmatic argument, with an aw-shucks, workin'-guy, just-folks attitude very typical of the American SF milieu. Silverberg doesn't claim superior knowledge of writerly principle (as he might well). He doesn't openly pose as a theorist or ideologue, but as a modest craftsman, offering rules of thumb.

I certainly don't scorn this offer, but I do wonder at it. Such modesty may well seem laudable, but its unspoken implications are unsettling. It seems to show an unwillingness to tackle SF's basic roots, to establish a solid conceptual grounding. SF remains pitchforked mercury, jelly nailed to a tree; there are ways to strain a living out of this ichor, but very few solid islands of theory.

Silverberg's proffered definition of science fiction shows the gooeyness immediately. The definition is rather long, and comes in four points:

- An underlying speculative concept, systematically developed in a way that amounts to an exploration of the consequences of allowing such a departure from known reality to impinge on the universe as we know it.

- An awareness by the writer of the structural underpinnings (the "body of scientific knowledge") of our known reality, as it is currently understood, so that the speculative aspects of the story are founded on conscious and thoughtful departures from those underpinnings rather than on blithe ignorance.

- Imposition by the writer of a sense of limitations somewhere in the assumptions of the story…

- A subliminal knowledge of the feel and texture of true science fiction, as defined in a circular and subjective way from long acquaintance with it.

SF is notoriously hard to define, and this attempt seems about as good as anyone else's, so far. Hard thinking went into it, and it deserves attention. Yet point four is pure tautology. It is the Damon Knight dictum of "SF is what I point at when I say `SF,'" which is very true indeed. But this can't conceal deep conceptual difficulties.

Here is Silverberg defining a "Story." "A story is a machine that enlightens: a little ticking contrivance… It is a pocket universe… It is an exercise in vicarious experience… It is a ritual of exorcism and purgation. It is a set of patterns and formulas. It is a verbal object, an incantation made up of rhythms and sounds."

Very fluent, very nice. But: "A science fiction story is all those things at once, and something more." Oh? What is this "something more?" And why does it take second billing to the standard functions of a generalized "story?"

How can we be certain that "SF" is not, in fact, something basically alien to "Story-telling?" "Science fiction is a branch of fantasy," Silverberg asserts, finding us a cozy spot under the sheltering tree of Literature. Yet how do we really know that SF is a "branch" at all?

The alternative would be to state that science fiction is not a true kind of "fiction" at all, but something genuinely monstrous. Something that limps and heaves and convulses, without real antecedents, in a conceptual no-man's land. Silverberg would not like to think this; but he never genuinely refutes it.

Yet there is striking evidence of it, even in Worlds of Wonder itself. Silverberg refers to "antediluvian SF magazines, such as Science Wonder Stories from 1929 and Amazing Stories from 1932… The primitive technique of many of the authors didn't include such frills as the ability to create characters or write dialogue… [T]he editors of the early science fiction magazines had found it necessary to rely on hobbyists with humpty-dumpty narrative skills; the true storytellers were off writing for the other pulp magazines, knocking out westerns or adventure tales with half the effort for twice the pay."

A nicely dismissive turn of phrase. But notice how we confront, even in very early genre history, two distinct castes of writer. We have the "real storytellers," pulling down heavy bread writing westerns, and "humpty-dumpty hobbyists" writing this weird-ass stuff that doesn't even have real dialogue in it. A further impudent question suggests itself: if these "storytellers" were so "real," how come they're not still writing successfully today for Argosy and Spicy Stories and Aryan Atrocity Adventure ? How come, among the former plethora of pulp fiction magazines, the science fiction zines still survive? Did the "storytellers" somehow ride in off the range to rescue Humpty Dumpty? If so, why couldn't they protect their own herd?

What does "science fiction" really owe to "fiction," anyway? This conceptual difficulty will simply not go away, ladies and gentlemen. It is a cognitive dissonance at the heart of our genre. Here is John Kessel, suffering the ideological itch, Eighties version, in SF Eye #1:

"Plot, character and style are not mere icing… Any fiction that conceives of itself as a vehicle for something called `ideas' that can be inserted into and taken out of the story like a passenger in a Toyota is doomed, in my perhaps staid and outmoded opinion, to a very low level of achievement."

A "low level of achievement." Not even Humpty Dumpty really wants this. But what is the "passenger," and what are the "frills?" Is it the "storytelling," or is it the "something more?" Kessel hits a nerve when he demands, "What do you mean by an 'idea' anyway?" What a difficult question this is!

The craft of storytelling has been explored for many centuries, in many cultures. Blish called it "a huge body of available technique," and angrily demanded its full use within SF. And in Worlds of Wonder, Silverberg does his level best lo convey the basic mechanics. Definitions fly, helpful hints abound. A story is "the working out of a conflict." A story "has to be built around a pattern of oppositions." Storytelling can be summed up in a three-word formula: "purpose, passion, perception." And on and on.

But where are we to find the craft of the "something more"? What in hell is the "something more"? "Ideas" hardly begins to describe it. Is it "wonder"? Is it "transcendence"? Is it "visionary drive," or "conceptual novelty," or even "cosmic fear"? Here is Silverberg, at the very end of his book:

"It was that exhilaration and excitement that drew us to science fiction in the first place, almost invariably when we were very young; it was for the sake of that exhilaration and excitement that we took up the writing of it, and it was to facilitate the expression of our visions and fantasies that we devoted ourselves with such zeal to the study of the art and craft of writing."

Very well put, but the dichotomy lurches up again. The art and craft of writing what, exactly? In this paragraph, the "visions and fantasies" briefly seize the driver's seat of the Kessel Toyota. But they soon dissipate into phantoms again. Because they are so ill-defined, so mercurial, so desperately lacking in basic conceptual soundness. They are our stock in trade, our raison d'etre, and we still don't know what to make of them.

Worlds of Wonder may well be the best book ever published about the craft of science fiction. Silverberg works nobly, and he deserves great credit. The unspoken pain that lies beneath the surface of his book is something with which the genre has never successfully come to terms. The argument is as fresh today as it was in the days of Science Wonder Stories.

This conflict goes very deep indeed. It is not a problem confined to the craft of writing SF. It seems to me to be a schism of the modern Western mindset, a basic lack of cultural integration between what we feel, and what we know. It is an inability to speak naturally, with conviction from the heart, of the things that Western rationality has taught us. This is a profound problem, and the fact that science fiction deals with it so directly, is a sign of science fiction's cultural importance.

We have no guarantee that this conflict will ever be resolved. It may not be resolvable. SF writers have begun careers, succeeded greatly, grown old and honored, and died in the shadow of this dissonance. We may forever have SF "stories" whose narrative structure is buboed with expository lumps. We may always have escapist pulp adventures that avoid true imagination, substituting the bogus exoticism that Blish defined as "calling a rabbit a 'smeerp.'"

We may even have beautifully written, deeply moving tales of classic human conflict—with only a reluctant dab of genre flavor. Or we may have the opposite: the legacy of Stapledon, Gernsback, and Lem, those non-stories bereft of emotional impact and human interest, the constructions Silverberg rightly calls "vignettes" and "reports."

I don't see any stories in Worlds of Wonder that resolve this dichotomy. They're swell stories, and they deliver the genre payoff in full. But many of them contradict Silverberg's most basic assertions about "storytelling." "Four in One" by Damon Knight is a political parable whose hero is a rock-ribbed Competent Man whose reactions are utterly nonhuman. "Fondly Fahrenheit" by Alfred Bester is a one-shot tour-de-force dependent on weird grammatical manipulation. "Hothouse" by Brian Aldiss is a visionary picaresque with almost no conventional structure. "The New Prime" by Jack Vance is six jampacked alien vignettes very loosely stitched together. "Day Million" showcases Frederik Pohl bluntly haranguing his readers. It's as if Silverberg picked these stories deliberately to demonstrate a deep distrust of his own advice.

But to learn to tell "good stories" is excellent advice for any kind of writer, isn't it? Well-constructed "stories" will certainly sell in science fiction. They will win awards, and bring whatever fame and wealth is locally available. Silverberg knows this is true. His own career proves it. His work possesses great technical facility. He writes stories with compelling opening hooks, with no extraneous detail, with paragraphs that mesh, with dialogue that advances the plot, with neatly balanced beginnings, middles and ends.

And yet, this ability has not been a total Royal Road to success for him. Tactfully perhaps, but rather surprisingly, Worlds of Wonder does not mention Silverberg's four-year "retirement" from SF during the '70s. For those who missed it, there was a dust-up in 1976, when Silverberg publicly complained that his work in SF was not garnering the critical acclaim that its manifest virtues deserved. These were the days of Dying Inside, The Book of Skulls, Shadrach in the Furnace—sophisticated novels with deep, intense character studies, of unimpeachable literary merit. Silverberg was not alone in his conclusion that these groundbreaking works were pearls cast before swine. Those who shared Silverberg's literary convictions could only regard the tepid response of the SF public as philistinism.

But was it really? Critics still complain at him today; take Geoff Ryman's review of The Conglomeroid Cocktail Party, a recent Silverberg collection, in Foundation 37. "He is determined to write beautifully and does… He has most of the field beaten by an Olympic mile." And yet: "As practiced by Silverberg, SF is a minor art form, like some kinds of verse, to be admired for its surface polish and adherence to form."

This critical plaint is a symptom of hunger for the "something more." But where are we to find its mercurial secrets? Not in the storytelling alembics of Worlds of Wonder.

Why, then, is Silverberg's book so very valuable to the SF writer of ambition? There are many reasons. Silverberg's candid reminiscences casts vital light into the social history of the genre. The deep structures of our subculture, of our traditions, must be understood by anyone who wants to transcend them. To have no "ideology," no theory of SF and its larger purposes, is to be the unknowing puppet of its unwritten rules. These invisible traditions are actually only older theories, now disguised as common sense.

The same goes for traditional story values. Blatant solecisms are the Achilles heel of the wild-eyed SF visionary. If this collection teaches anything, it's that one can pull the weirdest, wackiest, off-the-wall moves in SF, and still win big. But one must do this deliberately, with a real understanding of the consequences. One must learn to recognize, and avoid, the elementary blunders of bad fiction: the saidbookisms, the point-of-view violations, the careless lapses of logic, the pointless digressions, the idiot plots, the insulting clichés of character. Worlds of Wonder is a handbook for accomplishing that. It's kindly and avuncular and accessible and fun to read.

And some readers are in special luck. You may be one of them. You may be a young Robert Silverberg, a mindblown, too-smart kid, dying to do to the innocent what past SF writers have done to you. You may be boiling over with the Holy Spirit, yet wondering how you will ever find the knack, the discipline, to put your thoughts into a form that compels attention from an audience, a form that will break you into print. If you are this person, Worlds of Wonder is a precious gift. It is your battle plan.

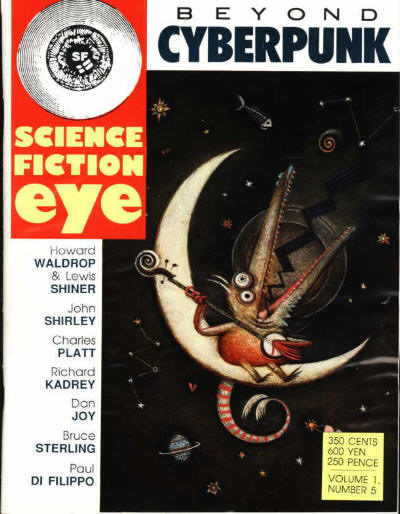

Slipstream

Catscan #5

Publication: Science Fiction Eye, #5

Date: July 1989

Editors: Stephen P. Brown, Daniel J. Steffan

Publisher: 'Til You Go Blind Cooperative

Price: $3.50

Pages: 108

Cover: Richard Thompson

In a recent remarkable interview in New Pathways #11, Carter Scholz alludes with pained resignation to the ongoing brain-death of science fiction. In the 60s and 70s, Scholz opines, SF had a chance to become a worthy literature; now that chance has passed. Why? Because other writers have now learned to adapt SF's best techniques to their own ends.

"And," says Scholz, "They make us look sick. When I think of the best `speculative fiction' of the past few years, I sure don't think of any Hugo or Nebula winners. I think of Margaret Atwood's The Handmaid's Tale, and of Don DeLillo's White Noise, and of Batchelor's The Birth of the People's Republic of Antarctica, and of Gaddis' JR and Carpenter's Gothic, and of Coetzee's Life and Times of Michael K… I have no hope at all that genre science fiction can ever again have any literary significance. But that's okay, because now there are other people doing our job."

It's hard to stop quoting this interview. All interviews should be this good. There's some great campy guff about the agonizing pain it takes to write short stories; and a lecture on the unspeakable horror of writer's block; and some nifty fusillades of forthright personal abuse; and a lot of other stuff that is making New Pathways one of the most interesting zines of the Eighties. Scholz even reveals his use of the Fibonacci Sequence in setting the length and number of the chapters in his novel Palimpsests, and wonders how come nobody caught on to this groundbreaking technique of his.

Maybe some of this peripheral stuff kinda dulls the lucid gleam of his argument. But you don't have to be a medieval Italian mathematician to smell the reek of decay in modern SF. Scholz is right. The job isn't being done here.

"Science Fiction" today is a lot like the contemporary Soviet Union; the sprawling possessor of a dream that failed. Science fiction's official dogma, which almost everybody ignores, is based on attitudes toward science and technology which are bankrupt and increasingly divorced from any kind of reality. "Hard-SF," the genre's ideological core, is a joke today; in terms of the social realities of high-tech post-industrialism, it's about as relevant as hard-Leninism.

Many of the best new SF writers seem openly ashamed of their backward Skiffy nationality. "Ask not what you can do for science fiction—ask how you can edge away from it and still get paid there."

A blithely stateless cosmopolitanism is the order of the day, even for an accredited Clarion grad like Pat Murphy: "I'm not going to bother what camp things fall into," she declares in a recent Locus interview. "I'm going to write the book I want and see what happens… If the markets run together, I leave it to the critics." For Murphy, genre is a dead issue, and she serenely wills the trash-mountain to come to Mohammed.

And one has to sympathize. At one time, in its clumsy way, Science Fiction offered some kind of coherent social vision. SF may have been gaudy and naive, and possessed by half-baked fantasies of power and wish-fulfillment, but at least SF spoke a contemporary language. Science Fiction did the job of describing, in some eldritch way, what was actually happening, at least in the popular imagination. Maybe it wasn't for everybody, but if you were a bright, unfastidious sort, you could read SF and feel, in some satisfying and deeply unconscious way, that you'd been given a real grip on the chrome-plated handles of the Atomic Age.

But now look at it. Consider the repulsive ghastliness of the SF category's Lovecraftian inbreeding. People retched in the 60s when De Camp and Carter skinned the corpse of Robert E. Howard for its hide and tallow, but nowadays necrophilia is run on an industrial basis. Shared-world anthologies. Braided meganovels. Role-playing tie-ins. Sharecropping books written by pip-squeaks under the blazoned name of established authors. Sequels of sequels, trilogy sequels of yet-earlier trilogies, themselves cut-and-pasted from yet-earlier trilogies. What's the common thread here? The belittlement of individual creativity, and the triumph of anonymous product. It's like some Barthesian nightmare of the Death of the Author and his replacement by "text."

Science Fiction—much like that other former Vanguard of Progressive Mankind, the Communist Party—has lost touch with its cultural reasons for being. Instead, SF has become a self-perpetuating commercial power-structure, which happens to be in possession of a traditional national territory: a portion of bookstore rackspace.

Science fiction habitually ignores any challenge from outside. It is protected by the Iron Curtain of category marketing. It does not even have to improve "on its own terms," because its own terms no longer mean anything; they are rarely even seriously discussed. It is enough merely to point at the rackspace and say "SF."

Some people think it's great to have a genre which has no inner identity, merely a locale where it's sold. In theory, this grants vast authorial freedom, but the longterm practical effect has been heavily debilitating. When "anything is possible in SF" then "anything" seems good enough to pass muster. Why innovate? Innovate in what direction? Nothing is moving, the compass is dead. Everything is becalmed; toss a chip overboard to test the current, and it sits there till it sinks without a trace.

It's time to clarify some terms in this essay, terms which I owe to Carter Scholz. "Category" is a marketing term, denoting rackspace. "Genre" is a spectrum of work united by an inner identity, a coherent esthetic, a set of conceptual guidelines, an ideology if you will.

"Category" is commercially useful, but can be ultimately deadening. "Genre," however, is powerful.

Having made this distinction, I want to describe what seems to me to be a new, emergent "genre," which has not yet become a "category."

This genre is not "category" SF; it is not even "genre" SF. Instead, it is a contemporary kind of writing which has set its face against consensus reality. It is a fantastic, surreal sometimes, speculative on occasion, but not rigorously so. It does not aim to provoke a "sense of wonder" or to systematically extrapolate in the manner of classic science fiction.

Instead, this is a kind of writing which simply makes you feel very strange; the way that living in the late twentieth century makes you feel, if you are a person of a certain sensibility. We could call this kind of fiction Novels of Postmodern Sensibility, but that looks pretty bad on a category rack, and requires an acronym besides; so for the sake of convenience and argument, we will call these books "slipstream."

"Slipstream" is not all that catchy a term, and if this young genre ever becomes an actual category I doubt it will use that name, which I just coined along with my friend Richard Dorsett. "Slipstream" is a parody of "mainstream," and nobody calls mainstream "mainstream" except for us skiffy trolls.

Nor is it at all likely that slipstream will actually become a full-fledged genre, much less a commercially successful category. The odds against it are stiff. Slipstream authors must work outside the cozy infrastructure of genre magazines, specialized genre criticism, and the authorial esprit-de-corps of a common genre cause.

And vast dim marketing forces militate against the commercial success of slipstream. It is very difficult for these books to reach or build their own native audience, because they are needles in a vast moldering haystack. There is no convenient way for would-be slipstream readers to move naturally from one such work to another of its ilk. These books vanish like drops of ink in a bucket of drool.

Occasional writers will triumph against all these odds, but their success remains limited by the present category structures. They may eke out a fringe following, but they fall between two stools. Their work is too weird for Joe and Jane Normal. And they lose the SF readers, who avoid the mainstream racks because the stuff there ain't half weird enough. (One result of this is that many slipstream books are left-handed works by authors safely established in other genres.)

And it may well be argued that slipstream has no "real" genre identity at all. Slipstream might seem to be an artificial construct, a mere grab-bag of mainstream books that happen to hold some interest for SF readers. I happen to believe that slipstream books have at least as much genre identity as the variegated stock that passes for "science fiction" these days, but I admit the force of the argument. As an SF critic, I may well be blindered by my parochial point-of-view. But I'm far from alone in this situation. Once the notion of slipstream is vaguely explained, almost all SF readers can recite a quick list of books that belong there by right.

These are books which SF readers recommend to friends: "This isn't SF, but it sure ain't mainstream and I think you might like it, okay?" It's every man his own marketer, when it comes to slipstream.

In preparation for this essay, I began collecting these private lists. My master-list soon grew impressively large, and serves as the best pragmatic evidence for the actual existence of slipstream that I can offer at the moment.

I myself don't pretend to be an expert in this kind of writing. I can try to define the zeitgeist of slipstream in greater detail, but my efforts must be halting.

It seems to me that the heart of slipstream is an attitude of peculiar aggression against "reality." These are fantasies of a kind, but not fantasies which are "futuristic" or "beyond the fields we know." These books tend to sarcastically tear at the structure of "everyday life."

Some such books, the most "mainstream" ones, are non-realistic literary fictions which avoid or ignore SF genre conventions. But hard-core slipstream has unique darker elements. Quite commonly these works don't make a lot of common sense, and what's more they often somehow imply that nothing we know makes "a lot of sense" and perhaps even that nothing ever could.

It's very common for slipstream books to screw around with the representational conventions of fiction, pulling annoying little stunts that suggest that the picture is leaking from the frame and may get all over the reader's feet. A few such techniques are infinite regress, trompe-l'oeil effects, metalepsis, sharp violations of viewpoint limits, bizarrely blase' reactions to horrifically unnatural events… all the way out to concrete poetry and the deliberate use of gibberish. Think M. C. Escher, and you have a graphic equivalent.

Slipstream is also marked by a cavalier attitude toward "material" which is the polar opposite of the hard-SF writer's "respect for scientific fact." Frequently, historical figures are used in slipstream fiction in ways which outrageously violate the historical record. History, journalism, official statements, advertising copy… all of these are grist for the slipstream mill, and are disrespectfully treated not as "real-life facts" but as "stuff," raw material for collage work. Slipstream tends, not to "create" new worlds, but to quote them, chop them up out of context, and turn them against themselves.

Some slipstream books are quite conventional in narrative structure, but nevertheless use their fantastic elements in a way that suggests that they are somehow integral to the author's worldview; not neat-o ideas to kick around for fun's sake, but something in the nature of an inherent dementia. These are fantastic elements which are not clearcut "departures from known reality" but ontologically part of the whole mess; "'real' compared to what?" This is an increasingly difficult question to answer in the videocratic 80s-90s, and is perhaps the most genuinely innovative aspect of slipstream (scary as that might seem).

A "slipstream critic," should such a person ever come to exist, would probably disagree with these statements of mine, or consider them peripheral to what his genre "really" does. I heartily encourage would-be slipstream critics to involve themselves in heady feuding about the "real nature" of their as-yet-nonexistent genre. Bogus self-referentiality is a very slipstreamish pursuit; much like this paragraph itself, actually. See what I mean?

My list is fragmentary. What's worse, many of the books that are present probably don't "belong" there. (I also encourage slipstream critics to weed these books out and give convincing reasons for it.) Furthermore, many of these books are simply unavailable, without hard work, lucky accidents, massive libraries, or friendly bookstore clerks in a major postindustrial city. In many unhappy cases, I doubt that the authors themselves think that anyone is interested in their work. Many slipstream books fell through the yawning cracks between categories, and were remaindered with frantic haste.

And I don't claim that all these books are "good," or that you will enjoy reading them. Many slipstream books are in fact dreadful, though they are dreadful in a different way than dreadful science fiction is. This list happens to be prejudiced toward work of quality, because these are books which have stuck in people's memory against all odds, and become little tokens of possibility.

I offer this list as a public service to slipstream's authors and readers. I don't count myself in these ranks. I enjoy some slipstream, but much of it is simply not to my taste. This doesn't mean that it is "bad," merely that it is different. In my opinion, this work is definitely not SF, and is essentially alien to what I consider SF's intrinsic virtues.

Slipstream does however have its own virtues, virtues which may be uniquely suited to the perverse, convoluted, and skeptical tenor of the postmodern era. Or then again, maybe not. But to judge this genre by the standards of SF is unfair; I would like to see it free to evolve its own standards.

Unlike the "speculative fiction" of the 60s, slipstream is not an internal attempt to reform SF in the direction of "literature." Many slipstream authors, especially the most prominent ones, know or care little or nothing about SF. Some few are "SF authors" by default, and must struggle to survive in a genre which militates against the peculiar virtues of their own writing.

I wish slipstream well. I wish it was an acknowledged genre and a workable category, because then it could offer some helpful, brisk competition to SF, and force "Science Fiction" to redefine and revitalize its own principles.

But any true discussion of slipstream's genre principles is moot, until it becomes a category as well. For slipstream to develop and nourish, it must become openly and easily available to its own committed readership, in the same way that SF is today. This problem I willingly leave to some inventive bookseller, who is openminded enough to restructure the rackspace and give these oppressed books a breath of freedom.

The Slipstream List

ACKER, KATHY - Empire of the Senseless

ACKROYD, PETER - Hawksmoor; Chatterton

ALDISS, BRIAN - Life in the West

ALLENDE, ISABEL - Of Love and Shadows; House of Spirits

AMIS, KINGSLEY - The Alienation; The Green Man

AMIS, MARTIN - Other People; Einstein's Monsters

APPLE, MAX - Zap; The Oranging of America

ATWOOD, MARGARET - The Handmaids Tale

AUSTER, PAUL - City of Glass; In the Country of Last Things

BALLARD, J. G. - Day of Creation; Empire of the Sun

BANKS, IAIN - The Wasp Factory; The Bridge

BANVILLE, JOHN - Kepler; Dr. Copernicus

BARNES, JULIAN - Staring at the Sun

BARTH, JOHN - Giles Goat-Boy; Chimera

BARTHELME, DONALD - The Dead Father

BATCHELOR, JOHN CALVIN - Birth of the People s Republic of Antarctica